One for the Record Books

World-champion drag racer who lost his vision uses a Boeing engineer’s audio guidance system to set a world record

During his college years, Boeing electrical engineer Patrick Johnson would spend most days on the University of Alabama in Huntsville campus, and most evenings under the hood of one of the many sports cars coming and going from his Decatur, Ala. home’s garage.

By the late 1990s, he had gained a following among local street car enthusiasts who’d seen his custom electronics up close, including controllers paired with nitrous oxide systems for timely jolts of power. For Johnson, who now works in Boeing’s AvionX division, and has spent his entire 20-year career at Boeing, it was the perfect melding of his two passions: fast cars and electronics.

In 2006, while already working full-time at Boeing in Huntsville, an acquaintance approached Johnson about a more complex challenge in the world of motorsports: developing a controller for an electronic fuel injection system used with 2,000-plus horsepower methanol-powered engines.

Within a few months, Johnson and his business partner installed their new system in a Pro Modified-class drag race car. It won its first race at a track in Montgomery, Alabama. At this event, Johnson met an accomplished drag racer and builder in his own right, Dan Parker.

After their win and introduction, Johnson and Parker stayed in touch, occasionally speaking by phone if Parker happened to be working on a car with one of Johnson’s systems.

Eventually, Johnson and his business partner took a step back from their project, which they had grown in their spare time. But it was on the evening of March 31, 2012, on his way home from supporting a customer at a race in Maryland, that Johnson heard the terrible news about his friend. Parker had been in a serious accident.

A 2 a.m. dream

On March 31, 2012, during a race at Alabama Dragway in the town of Steele, Parker was nearing the end of the one-eighth-mile (201-meter) track when his modified 1963 Chevrolet Corvette veered into a concrete retaining wall at about 180 mph (289 kmh). The car burst into flames. Parker narrowly survived the wreck. Two weeks later, he awoke from a medically induced coma with no memory of the accident and having lost his vision. He was told that swelling in his brain had damaged his optic nerve.

For Parker, now 51 and a resident of Columbus, Georgia, racing hadn’t just been a hobby or a vocation before his accident, but a way of life for his family. His father began racing cars at 16. His mother raced at the local dragstrip — even when she was eight months pregnant with Parker. When Parker was eight years old, his dad entered him in his first motorcycle race, and Parker did not disappoint: he finished second in the mini-bike class. At 16, he started racing cars and also building them. As a driver, he would eventually win a Dixie Pro Stock championship and the 2005 ADRL Pro Nitrous world championship title.

In the days, weeks, and months after his spring 2012 accident, Parker struggled to recover from his injuries and come to terms with his new life. As he tells it, he fell into a deep depression.

Late one night in October 2012, Parker laid in bed thinking about his late brother, Chris, who had died tragically of alcoholism three years earlier. When Parker fell asleep at around 2 in the morning, he saw himself racing on the legendary Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. He was driving a motorcycle. He woke up the next morning and told his fiancée Jennifer about the dream — and that he wanted to become the first blind driver to compete in the time trials on the salt flats. While Jennifer was supportive, not everyone in his immediate orbit bought into the plan. He did his best to tune them out.

“It saved my life,” Parker said during a recent interview about his new goal. “It gave me a purpose.”

The first challenge was to design an audio guidance system that would help Parker steer. In the past, other blind land-speed racers had relied on steering instructions conveyed via two-way radios from team members trailing them in a chase car or helicopter. Parker wanted to drive without the help of a sighted person.

“I thought, ‘Well, who’s the smartest person I know?’” Parker said. “It was Patrick Johnson. I called him and he said ‘That’s easy. I can do it. Start building your motorcycle.’”

With Johnson’s assurances, Parker got to work designing a 70cc, three-wheeled motorcycle. He built most of it in his backyard shop with a mix of parts he purchased himself and those donated to the project. Others volunteered their labor to help, and sponsors also supported the project.

By June 2013, the motorcycle was ready. Parker named it the Christopher Scott Special after his late brother Chris.

First time out

That summer, Parker and Johnson travelled to a regional airport in North Alabama, where Parker received permission to test out his new motorcycle and Johnson’s audio guidance system. It didn’t take long for Parker to make headway.

“He was able to travel down the 3,600-foot (1,097-meter) runway completely by himself and was fairly straight,” Johnson recalled. “That was a big moment in the project — he knew it was possible.”

They returned a few more times to practice and to tweak the way Johnson’s system transmitted information into the stereo headphones Parker wore under his helmet.

The system relied on a high-end GPS sensor and computer on Parker’s motorcycle. With each visit to the runway, Johnson would drive to the start and finish lines and plot their locations, creating a virtual centerline for Parker that ran between them. The idea was for the sensor to then sound audio tones for Parker if he was veering off-center in one direction or the other. Tones played in his left ear would indicate that he was drifting to the left, and vice versa. The louder the tone, the further from the centerline. It was still up to Parker to make the necessary corrections himself if needed.

Johnson included safety features like the ability to cut the motorcycle’s engine remotely from a chase car. The system was also programmed to cut the engine whenever the motorcycle crossed the finish line, or if Parker’s motorcycle lost communication with Johnson’s laptop in the chase car.

In August 2013, just 16 months after the accident in Steele, Parker arrived at the Bonneville Salt Flats and completed the half-mile course three times. His motorcycle topped out at 55.331 mph (89 kmh) on the compacted salt, and according to an account published on the front page of the Salt Lake Tribune, Parker was only “slightly wavering” during his runs.

A year later, Parker returned to the Salt Flats for its time trials and made a record one-mile pass (1.6 kilometers) in his motorcycle. His top speed was about 62 mph (99.7 kmh), a record in his class of motorcycles that still stands today.

Back behind the wheel

On March 31, 2015, the third anniversary of his accident, Parker graduated from the Louisiana Center for the Blind, which equips students with the skills they need to navigate the world with self-sufficiency and independence. By 2018, Johnson and Parker began talking every month or so about Parker’s newest ambition: becoming the world’s fastest blind man.

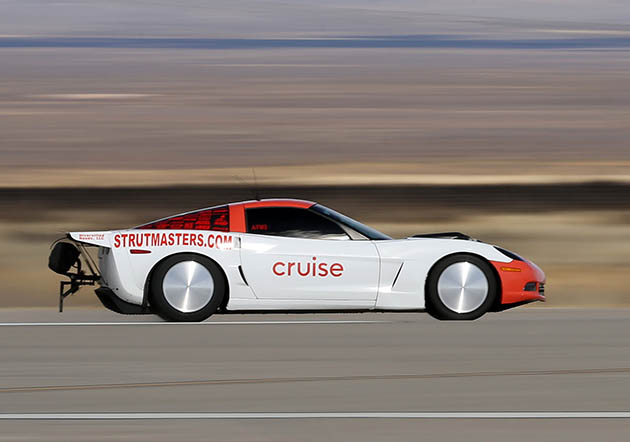

At the time, Driver Mike Newman of the United Kingdom was the record holder, having gone 200.9 mph (323.3 kmh). Parker was intent on breaking Newman’s record. He asked his uncle to check out a flood-salvaged 2008 Corvette in Oklahoma City, which Parker purchased for $4,500. It had no motor and no interior. “To say she had a hard life would be an understatement,” he said.

Once again, Johnson was on board to help design a new audio guidance system. Before Parker’s injury, Johnson hadn’t known anyone who was blind. In becoming close with Parker, he was inspired by what Parker had managed to achieve.

“He was now doing what he loved again. He was back in his world again — in a different way, but he was there,” Johnson said. “Seeing that impact, that became the driving force to make Dan succeed.”

Parker began designing and rebuilding the Corvette from the ground up in his 600-square-foot backyard shop. Once again, those in his circle donated parts and volunteered their time. Sponsors also helped fund the effort.

Given the new target speeds involved — in which Dan and his Corvette would be clearing the equivalent of a football field each second when approaching 200 mph (321.8 kmh) —a new and more advanced navigation system was needed to track Dan’s real-time position against a virtual centerline.

With an early version of the new car-based audio guidance system installed, Johnson and Parker decided to get several speed events under their belts in the lead-up to a spring 2022 record attempt.

In March 2020, late-night television legend Jay Leno and the producers of his NBC show “Jay Leno’s Garage” caught wind of Parker’s story and produced a television segment about his remarkable journey. The episode aired two months later, when Leno’s ride-along and interview with Parker was paired with a feature on Elon Musk’s Cybertruck.

'Bawling like a baby'

Parker and his team chose the week of March 31, 2022 — the 10-year anniversary of Parker’s accident — as the week in which they would attempt to break the Guinness World Records title for “Fastest Speed for a Car Driven Blindfolded,” a goal four years in the making. (No category exists for drivers who are blind or who have low vision.)

They chose Spaceport America in New Mexico for the record attempt, where the runway is 12,000 feet (3,657 meters) long and 200 feet (60.9 meters) wide. The National Federation of the Blind helped sponsor Parker’s team and reserved the runway from March 29-31.

On Tuesday and Wednesday of that week, Parker and his team were hampered by 40- and 50-mph (64- and 80-kmh) winds, precluding the possibility of a pass. Finally, that Thursday, with crosswinds of 15-20 mph (24-32 kmh), Parker and his team received the green light. Minor issues with the car delayed the first official attempt until 4:45 that afternoon — 15 minutes before the team’s reservation would expire.

Before his accident, Parker had driven as fast as 220 mph (354 kmh). Visual cues outside his car would give him the feedback needed to steer and make corrections, which all came naturally. Now, sitting in his custom-built Corvette with three mufflers, molded earbuds, and helmet, Parker estimates that 80% of all outside noise was cancelled out.

To steer at high speeds without visual cues or most aural feedback required what Parker calls “an extreme exercise in concertation,” with all of his trust placed in Johnson’s system. With each tone came a judgement call: to continue on the same course if he was still generally heading straight while parallel to the centerline, or to make a minor steering adjustment without overcorrecting.

As Parker hit the accelerator for his first pass, Johnson sat in a trailer near the runway monitoring his speed and position on a laptop. Johnson admits he “isn’t one to get outwardly excited.” So when he saw Parker reach 212 mph (341 kmh) before crossing the finish line, just two thoughts came to mind: “Dan did it. Now let’s do it again.”

To make the record official, Parker needed to turn the car around and top Newman’s record a second time within a one-hour window, including the time needed to cool and prep the car for another run, this time facing the wind. The average of his two top speeds that day — 211.043 mph (339.64 kmh) — would set a new Guinness World Records mark.

Sitting in the car while waiting for his record to be certified, Parker recalls feeling immense relief. Above all else, he had worried about disappointing his 12-person crew. The team was comprised of volunteers from across the country, many of whom had taken vacation days to help Parker.

After an adjudicator with Guinness World Records validated the runs — having watched footage taken within the Corvette showing that the crew member sitting beside Parker hadn’t so much as touched the car’s dual steering wheel — Parker felt pure jubilation. The significance of the accomplishment was finally setting in.

“I was bawling like a baby,” Parker said. “Everything emotional, it was all hitting.”

A new (and slower) end goal

During a phone interview from his home in Georgia on a recent afternoon, Parker admits that back in late 2012, even after dreaming of racing the Bonneville Salt Flats, he wasn’t yet thinking about inspiring others. He was just hoping his new goal would help him get through a difficult time.

In teaming with the National Federation of the Blind on his record-setting runs at Spaceport America, part of the organization’s longstanding Blind Driver Challenge, he wanted to demonstrate that people who are blind or who live with low vision are no less capable than their sighted peers in the workplace, classroom, or on the racetrack with the right accessible technology.

Most days, Parker is living out that message in his home workshop. He hand-machines aluminum pens and razors and sells them on his website, theblindmachinist.com. His milling machine is linked to a digital readout box, a kind of numerical display showing the cutting table’s exact position.

Johnson helped Parker wire the readout to speakers and has programmed it to speak the measurements to Parker to within half-a-thousandth of an inch, or about one-sixth the width of a piece of notebook paper. By pressing one of two foot pedals that Johnson has also connected to the digital readout box, Parker can hear the location of his tool on either the table’s horizontal or vertical axis before each cut.

To take the message further, Parker and Johnson will be teaming on a new challenge. Parker plans on participating in the 2023 Bicycle Ride Across Georgia (BRAG) next June. The aim is to show how technology can expand mobility options for blind people.

Johnson is working on designing a bicycle that can gather and process GPS data on the go while leaving an electric breadcrumb trail for a recumbent bicycle that Parker will be pedaling behind it. The lead bike will provide the steering data to autonomously turn Parker’s handlebars, while Parker will be doing the pedaling and braking himself. He expects to ride 50 or so miles per day during the BRAG to reach this latest finish line.